State of Center City: Highlights

Recovery

By the end of April, pedestrian volumes downtown had returned to 86% of pre-pandemic levels. Center City enjoys more sidewalk vitality than many other downtowns because of the diversified nature of land-use – office, health care and education, hotels and retail – with total employment accounting for 42% of Philadelphia’s jobs. Total population in apartments, condominiums and single-family units is nearly 70,000 in the core, from Vine to Lombard, river to river, with another 132,000 living in the adjacent neighborhoods that make up Greater Center City. This has been the fastest growing residential area of Philadelphia since 2000, with more than 17,000 units of new housing currently under construction or permitted.

To date, 80% of retail and restaurant storefronts within Center City District boundaries are open or have obtained tenants. Performing arts and cultural institutions are fully open. Tourism and conventions have rebounded, with the average daily room rate in Center City hotels rising from $156 in 2020 to $182 in 2021, just 10% below 2019 levels. The combination of Center City shoppers and visitors attained 87% of pre-pandemic levels in April, while non-resident workers were at 49%.

During the first quarter of 2022, Philadelphia as a whole had restored 70% of the 126,500 jobs lost in the first two months of the pandemic. The biggest rebounds were in the office, health care and education sectors.

At the same time, our educational and health-care institutions have been securing federal research grants and venture capital in the burgeoning fields of cell and gene therapy, which is spurring life sciences development in University City that’s spilling over into Center City. Research institutions in Philadelphia received $1.1 billion in National Institutes of Health funding in 2021, fourth highest in the nation.

Challenges

In February 2022, we were still 38,500 jobs below pre-pandemic levels. At 70% job recovery, Philadelphia lags the region, which has restored 84% of lost pre-pandemic jobs, and the nation, which has regained 87% of lost jobs. Jobs that are lagging are moderate- and low-wage jobs that cannot be performed remotely.

Philadelphia’s slow recovery mirrors the slow growth experienced from 2010 to 2019, when Philadelphia added private sector jobs at the rate of 1.5% per year, 26th among counties covering the 30 largest cities, behind Detroit (1.7%) Washington (2.1%,), Boston (2.6%) and New York (2.8%).

In the last decade, Philadelphia also added a disproportionate share of low-wage jobs, as the suburbs and our peer cities grew more family-sustaining jobs. Boston, New York and Washington also lost 85% to 90% of their 1970 manufacturing jobs, but they replaced them with a broad range of post-industrial jobs. In 2019, Boston had 31% more wage and salary jobs than in 1970, New York had 20% more and Washington had 18% more. Philadelphia was 21% below 1970 job levels in 2019 with a lower density of businesses and a lower concentration of Black and brown businesses than peer cities.

Philadelphia residents are thus less likely to be employed full time, with household incomes that are lower and housing affordability challenges that are greater. As a result, we have the highest poverty rate of the 10 largest U.S. cities.

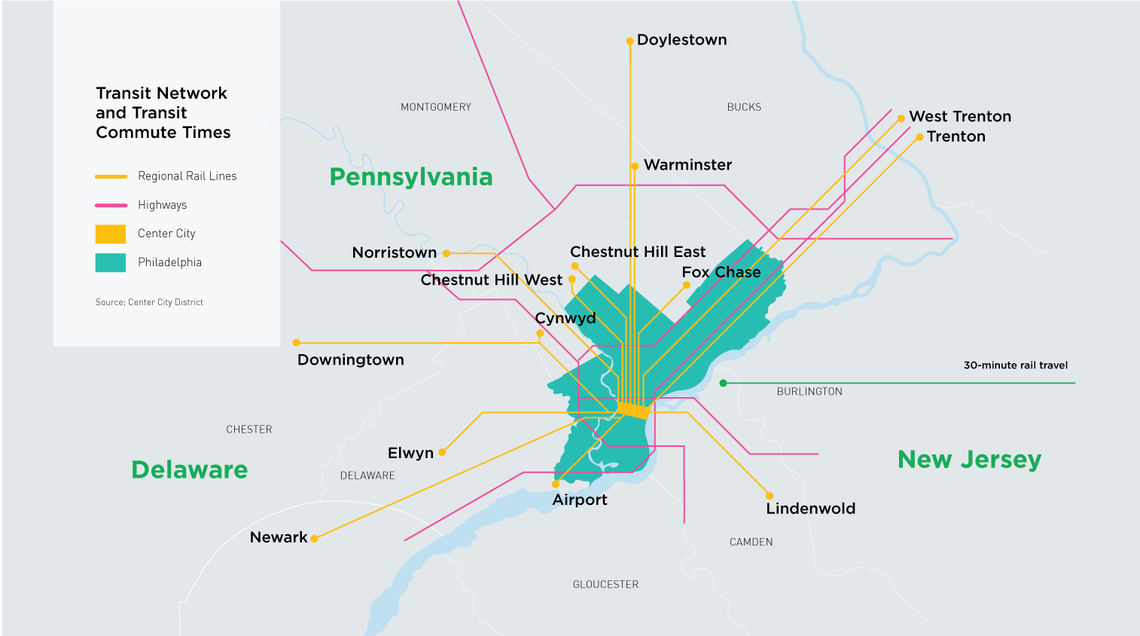

The high concentration of Philadelphia’s total jobs is in Center City (42%) and University City (11%) at the center of a multimodal regional transit system. The diverse nature of those jobs means that downtown job growth has citywide benefits, even as Philadelphia needs to grow businesses and jobs citywide.

What Needs To Be Done

(1) Increasing job growth and business density citywide reduces unemployment and poverty. In 1970, Philadelphia’s poverty rate was almost identical to Boston, New York and Washington. But in the next three decades as those cities added new jobs, Philadelphia lost 255,000 jobs and 428,000 working- and middle-class residents. The actual number of people in poverty rose by 42,000 from 1970 to 2000, but we lost 10 times as many working and middle-class residents. We have the highest poverty rate because we have the slowest job growth and the lowest density of businesses. When we grew jobs in the last decade, poverty declined.

In Center City, maximizing the return of office workers will restore employment in transportation, building services, retail and restaurants, jobs that can’t be performed remotely.

(2) Entrepreneurial activity and business expansion require investments in infrastructure, education, job training and access to capital for Black and brown business. Supporting the growth of small and medium sized business and their ability to connect with the purchasing power of large businesses and institutions creates new opportunity for residents in every neighborhood.

(3) Reduce over-dependence on wage and business taxes: Philadelphia remains overly dependent on wage and business taxes that create disincentives for firms and workers to locate or expand in the city. The reliance on wage taxes that dropped precipitously during the pandemic, also meant that Philadelphia used a far larger share of federal American Rescue Plan funds to close budget gaps than cities primarily supported by the more stable real estate tax. As a result of slow job growth and high poverty, far too much of the City’s budget must be devoted to problems related to poverty, unemployment and crime and not enough is invested in economic development, parks, libraries and other public amenities.

(4) Back-to-basics: Throughout Philadelphia there is a renewed interest in the basics — clean and safe— as the pendulum returns to a common-sense middle ground about reformed, but enhanced, public safety in cities across the country. For 31 years, Center City District has focused on the basics, creating a clean, safe and animated public environment. Our 148 on-street staff were essential workers who continued throughout the pandemic. Expanded public investment in our neighborhoods in cleaning, community policing and in parks and quality public schools will restore confidence and optimism and create the environment for more robust and inclusive job growth.